Mount Aigoual, the second highest peak in the Cévennes, is a wet place. Annual rainfall averages around 2 m per year (yes metres – not centimeters). In an a very wet year, the total annual accumulation could reach 4 m. The name Aigoual derives from the root word “aiga” meaning “water” in a number of romance languages and dialects. No surprise there.

Local geology is complex – granite bedrock, karst topographies and schist. Several rivers arise on and around the peak. One of them is called “Le Bonheur” (Happiness) ”.

The Bonheur meanders across a flat granite plateau and filters through various bogs. At a point near the town of Camprieu, the river flows off the granite bedrock into an area of karst limestone. Soon after, the river enters a sizable cave and about 100 metres into the cave, the river disappears underground. This disappearance point is known as “la Perte” – the loss. In the picture, we see the entrance to the cave, and in the distance a sun-lit area resulting from a partial roof collapse deep in the cave.

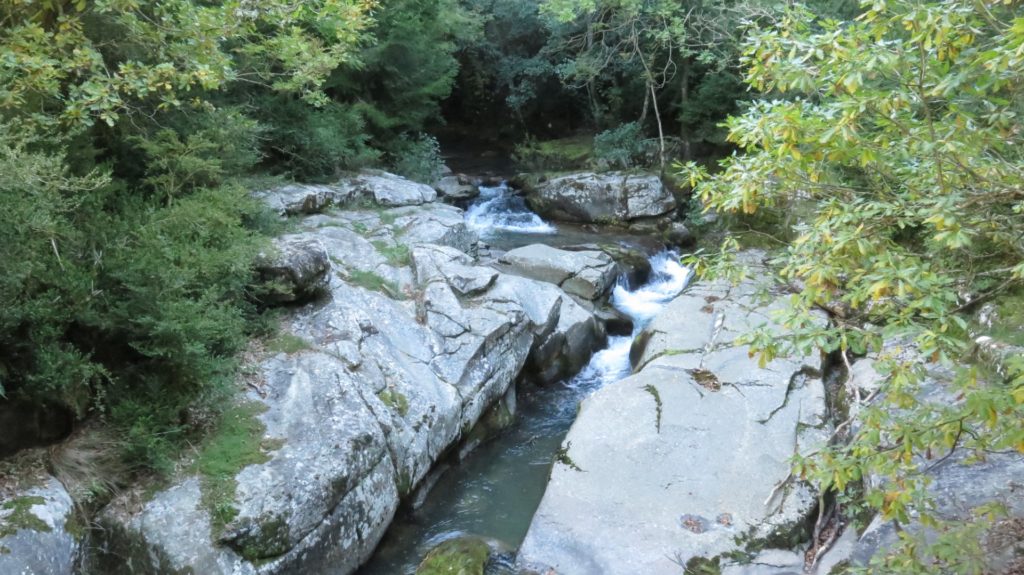

Around 500 m away, at the bottom of an imposing limestone cliff a river emerges at the base of a huge vertical diaclase*. Same river ? The answer is yes. This was proven by some of the earliest french cave divers in the late 19th century by traversing the underground river bed from end to end.

Where the river emerges from the cliff face it is now called the “Bramabiau”, meaning the “braying of bulls” named for the noise of the surging waterfalls.

So happiness became a raging bull… It seems like the river, entering a zone of karst with its numerous underground cavities ended up by finding or creating a way through to the base of the cliff where it emerges at an altitude around 70 metres lower. The section between the perte and the emergence of the river will eventually become a ravine as the cavities grow and surface structures collapse.

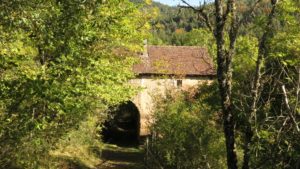

This hike starts from the small town of Camprieu and heads steadily downhill into the Aigoual forest, following ancient cobbled paths through a humid valley. Eventually the path emerges near an old stone farmstead – imposing but nevertheless abandoned. A few paces further along you reach the remote and also abandoned village of Saint Sauveur. The village consists of a substantial church, a set of fortified farm buildings and a cemetery. The whole impression is strange : why such a church and village in the middle of nowhere ? The answer, it seems is that the surrounding land was very fertile, and subsistence living from agriculture was feasible.

This village, about 4 km from Camprieu and in a difficult to reach spot, was the original centre of town, but was progressively abandoned in the late 19th to early 20th century in favour of Camprieu – easier to reach by road and location of a new church. The abandoned village was eventually purchased by the French forest management authority (the ONF) and is now at the centre of a fine arboretum. From Saint Sauveur, the trail runs uphill back towards Camprieu and very close to the diaclase and the raging bull. We decided to visit. Tickets are purchased near the highway and the guide takes you down to the base of the cliff, into the diaclase and through a labyrinth of galleries, mini-canyons, waterfalls and caverns created by raging waters. Of course – visits only available when the water is not raging and this means guided tours only – no free roaming. This site – the Abîme de Bramabiau – is open to visitors from spring to autumn but closed in winter (too much water and anyway no visitors).

After the guided tour (taking about 90 minutes) the route takes us back to Camprieu passing close to the Perte du Bonheur. We make a short detour to see where the river disappears underground. The site is almost as impressive as the Diaclase.

This hike, in summary, offers the special ingredients sought by many hikers : walking, history, nature and surprises…

- Diaclase : A joint or a fault line in bedrock, usually understood to be geologically inactive.