Starting from 1 February 2022, the French mapping institute (IGN : Institut Géographique National renamed to Institut national de l’information géographique et forestière) implemented new API’s and new API keys for use of their WMTS mapping service. As a result, IGN base maps may have been unavailable on this site for several days, It took some time to understand the implications and make the necessary software changes. At present, most of the necessary modifications are complete and maps should display properly.

Abandoned rail lines in the Uzège district

The group of trails described in this article allow interested walkers to see a number of places where remnants of 19th century railroad lines are still visible, sometimes abandoned, but often reused as roads, storage depots and private houses.

Three rail lines crossed the Uzège district in the 19th and early 20th century. These were :

- A line from Beaucaire to Le Martinet. This one was built to transport coal from the Auzonnet valley to the Rhône river port at Beaucaire. Authorised in 1875, the line opened two sections in 1880 – one from Uzès to Remoulins and a second from Le Martinet to Les Fumades. These lines could immediately function as branches on pre-existing services. In 1883, the remaining sections were opened. Passenger traffic was suspended in 1938 and sections were progressively closed up to 2006. In 2018 after final administrative closures, several sections of the line – in particular from Beaucaire to Uzès – have been converted to bike and pedestrian walkways. The sections of this line explored in the following walking routes, all to the west of Uzès, have yet to be rehabilitated. Major engineering works still visible on this route include the viaducts in Euzet and the 400 m rail tunnel in Celas, both of which are visited by the walking routes below.

- A line from Laudun-L’Ardoise to Alès : Contrary to the other 2 lines, both granted to the Paris-Lyon-Mediterrannee rail operator, this concession was granted to ARM (Alais-Rhône-Mediterranee). Ostensibly this would be to compete with the PLM operation in transporting freight to the Rhône via an alternate, quicker route. But the line may have been unsuccessful from the start as the terminus in Alès was not that close to coal mines. In fact the terminal station was in the Conilhères area of Alès, near the main PLM station, but due to commercial disagreements this line was not interconnected with the Cévennes mainline. Ultimately, like the others, the line was closed to passengers in 1938 and totqlly closed to freight by 1954. Some references say this line was never profitable. The modern highway between Bagnols and Alès uses a substantial portion of this line between Seynes and Brouzet. Visible remains of this line include the Saint-Laurent station – now a private home.

- An 18.9 km line from Uzès station to Nozières connecting Uzes to the main Cévennes route (Nîmes through Alès to Clermont-Ferrand). Construction of the line was authorised in 1875 and it was opened in 1883. The line was closed to passengers in 1930 and steel rails were removed from the line during the second world war for other uses. The early closing of this line suggests that it was never particularly profitable. Major engineering works included a viaduct over the road from Uzès to Arpaillargues – still visible today – and a bridge over the Gardon river near Moussac. The Moussac bridge foundation was re-used in the late 20th century to build a new highway bridge over the Gardon river.

The interactive map below displays the approximate route of each of these 3 lines in the western Uzège district. The altitude profiles are approximate only.

Approximate rail routes

Section of line from Laudun to Alès

Complete route Uzès to Nozières

Section of Beaucaire-Martinet line

The walking routes

Exploring the line from Beaucaire to Le Martinet :

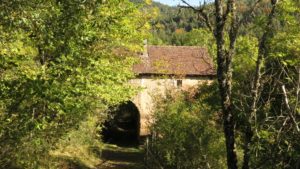

These 3 walking routes explore sections of the line from Beaucaire to Le Martinet. West of Uzès, the line traverses Montaren, Serviers, Foissac, Saint-Maurice, Euzet and Saint Just. The major civil engineering sites are the viaducs in Euzet and the tunnel in Celas. The walking trail in the Bouscarasse area follows the old rail route for several km through a wet forest where it is possible to observe the numerous cuts and embankments needed to cross this wet area. The tunnel in Celas can be traversed on foot (rechecked in 2021) but the poor light in the center of the tunnel means a flashlight or forehead lamp is advisable.

Exploring the Uzès to Nozières line

The loop below starts in the small hamlet of Aureillac and after passing a section of forest, reaches a foot bridge over a deep cut used by the line to limit roadbed slopes. Further along this walk it is possible to see a significant viaduct over the main Uzès-Arpaillargues highway (slightly off the walking route). Both this structure and the preceding deep cut trench allowed the track to maintain a fairly uniform slope as it climbed out of the Uzès station to the higher ground around Arpaillargues.

A short walk near the line from Laudun to Alès

On this walk, it’s possible to see a large former rail station now converted to a private home. Near the station a number of barns, garages and sheds seem to hark back to the railroad days. It looks like there was a substantial freight operation around this station near Saint-Laurent-la-Vernède. There is an abandoned ocre quarry along the route. Perhaps freight from this quarry was shipped via the Saint-Laurent station .

Walk and look

In many cases, the former rail route has been converted to road or track, sometimes to bicycle paths. Old stations, identifiable by their distinct 19th century “railroad” style are still in use almost everywhere – as private dwellings. Apart from stations, there were various technical buildings along these tracks – some served as residences for barrier guards. Some of these are ruined – an example is visible in the Bouscarrasse area. Bridge foundations have been reused for roadway. A substantial section of the D6 from Bagnols to Alès reuses the old track bed near the Seyne cliffs. In other cases, for example near Maruejols-les-Bois, the ballast has been removed and the track right of way is now a muddy mess. In a number of cases the rail road passes over other roads or tracks. In many cases the abutments are present but the bridge deck has disappeared. The viaducts in Euzet are large and apparently unmaintained. Sooner or later walking across these viaducts will become impossible for safety reasons. The rail tunnel in Celas is quite passable (with a flash light) but also apparently unmaintained. If a section of the tunnel roof were to collapse, the tunnel will certainly be closed. It is a testimony to the solid engineering works of the 1880’s that these things are still standing. Remember that most of these structures would have been built without mechanical digging, lifting, or earth moving equipment.

The pictures in this article were mostly taken between 2020 and 2021. The author personally walked these routes in 2021. Never-the-less, a walking route is never permanent. Routes can be closed, re-routed. Tunnels and bridges may become unsafe and impassable etc. Use the data with care.

Vineyards and Camisards

The little town of Castelnau-Valence is surrounded by many hectares of vineyards sometimes seeming to fill the horizon. An autumn walk on a sunny day provides a stunning display of contrasts and colors.

But there is history here too. The castle on a hill at Castelnau – about 1.5 km from the town centre was involved in a famous but tragic episode during Camisard wars of the early 18th century.

In 1685, Louis XIV decided that he’d had enough of the Calvinist Protestants (known as Huguenots). He issued a decree forbidding the practice of the Calvinist religion and providing for the destruction of Calvinist churches and closure of schools. Huguenots caught secretly practicing their religion were subject to persecution, confiscation, imprisonment and execution.

Around 1700, in the Cévennes hills, long a Huguenot stronghold, groups of young men (the so called Camisards) entered into guerrilla style armed resistance, banding together to attack Catholic villages and churches, royal troops and other symbols of the repressive state. Their raids tool place all though the Cévennes including the high plateaus, the foothills and the garrigue areas around Uzès, Aigaliers, Alès, and Castelnau-Valence.

Pierre Laporte was a Camisard, a preacher and a good fighter. Born in Mialet, he was involved in many skirmishes and attacks between 1699 and 1704. But by mid 1704 a number of the Camisard chiefs had decided to give up the fight and leave France in exile. Not Pierre Laporte. He was to fight on until, on a day in August 1704, someone tipped off the royal troops that he was hiding out in the castle at Castelnau. Laporte was able to flee just before the arrival of the troops but, with no lead time on his pursuers, he was caught and killed in a valley nearby. A memorial now stands near the site.

This walk starts at the playground in Valence and passes by a large 19th century windmill, recently renovated. The windmill was built in the 19th century to pump water from a local well and supply fountains in the nearby towns of Saint-Dezery and Valence. Around 1940, wind power was replaced by electrical power and by 1956 the pumps were no longer needed. The windmill remains in good shape due to renovations in the early 21st century.

After the windmill, there are hectares of vineyards until reaching the Pierre Laporte Memorial. After the memorial, south of the Castelnau grounds there is a remarkable tree – a prickly juniper. This species is very common in the Mediterranean region and is usually a shrub or a small tree, The specimen at this way-point is 13 metres tall with a 4-5 metre trunk. The tree is thought to be up to 1000 years old.

Finally reaching a hilltop on the highway there is a closer view of the Castelnau castle (now private), site of the historical incident mentioned above.

Happiness Lost

Mount Aigoual, the second highest peak in the Cévennes, is a wet place. Annual rainfall averages around 2 m per year (yes metres – not centimeters). In an a very wet year, the total annual accumulation could reach 4 m. The name Aigoual derives from the root word “aiga” meaning “water” in a number of romance languages and dialects. No surprise there.

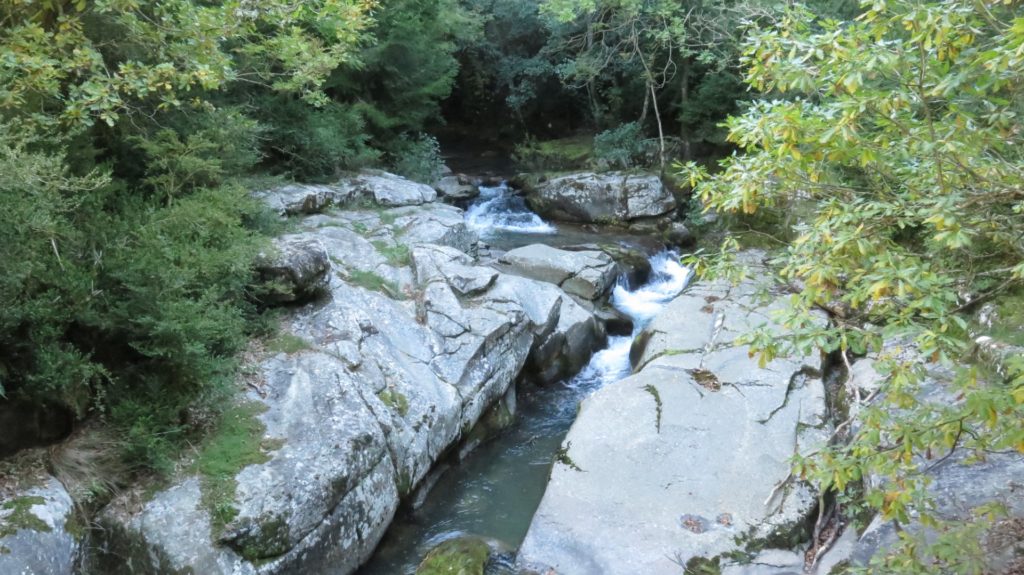

Local geology is complex – granite bedrock, karst topographies and schist. Several rivers arise on and around the peak. One of them is called “Le Bonheur” (Happiness) ”.

The Bonheur meanders across a flat granite plateau and filters through various bogs. At a point near the town of Camprieu, the river flows off the granite bedrock into an area of karst limestone. Soon after, the river enters a sizable cave and about 100 metres into the cave, the river disappears underground. This disappearance point is known as “la Perte” – the loss. In the picture, we see the entrance to the cave, and in the distance a sun-lit area resulting from a partial roof collapse deep in the cave.

Around 500 m away, at the bottom of an imposing limestone cliff a river emerges at the base of a huge vertical diaclase*. Same river ? The answer is yes. This was proven by some of the earliest french cave divers in the late 19th century by traversing the underground river bed from end to end.

Where the river emerges from the cliff face it is now called the “Bramabiau”, meaning the “braying of bulls” named for the noise of the surging waterfalls.

So happiness became a raging bull… It seems like the river, entering a zone of karst with its numerous underground cavities ended up by finding or creating a way through to the base of the cliff where it emerges at an altitude around 70 metres lower. The section between the perte and the emergence of the river will eventually become a ravine as the cavities grow and surface structures collapse.

This hike starts from the small town of Camprieu and heads steadily downhill into the Aigoual forest, following ancient cobbled paths through a humid valley. Eventually the path emerges near an old stone farmstead – imposing but nevertheless abandoned. A few paces further along you reach the remote and also abandoned village of Saint Sauveur. The village consists of a substantial church, a set of fortified farm buildings and a cemetery. The whole impression is strange : why such a church and village in the middle of nowhere ? The answer, it seems is that the surrounding land was very fertile, and subsistence living from agriculture was feasible.

This village, about 4 km from Camprieu and in a difficult to reach spot, was the original centre of town, but was progressively abandoned in the late 19th to early 20th century in favour of Camprieu – easier to reach by road and location of a new church. The abandoned village was eventually purchased by the French forest management authority (the ONF) and is now at the centre of a fine arboretum. From Saint Sauveur, the trail runs uphill back towards Camprieu and very close to the diaclase and the raging bull. We decided to visit. Tickets are purchased near the highway and the guide takes you down to the base of the cliff, into the diaclase and through a labyrinth of galleries, mini-canyons, waterfalls and caverns created by raging waters. Of course – visits only available when the water is not raging and this means guided tours only – no free roaming. This site – the Abîme de Bramabiau – is open to visitors from spring to autumn but closed in winter (too much water and anyway no visitors).

After the guided tour (taking about 90 minutes) the route takes us back to Camprieu passing close to the Perte du Bonheur. We make a short detour to see where the river disappears underground. The site is almost as impressive as the Diaclase.

This hike, in summary, offers the special ingredients sought by many hikers : walking, history, nature and surprises…

- Diaclase : A joint or a fault line in bedrock, usually understood to be geologically inactive.