Balazuc is a picturesque village sitting on a rocky hillside on the left bank of the Ardèche river not too far from Aubenas – and about 100 km north of Nîmes.

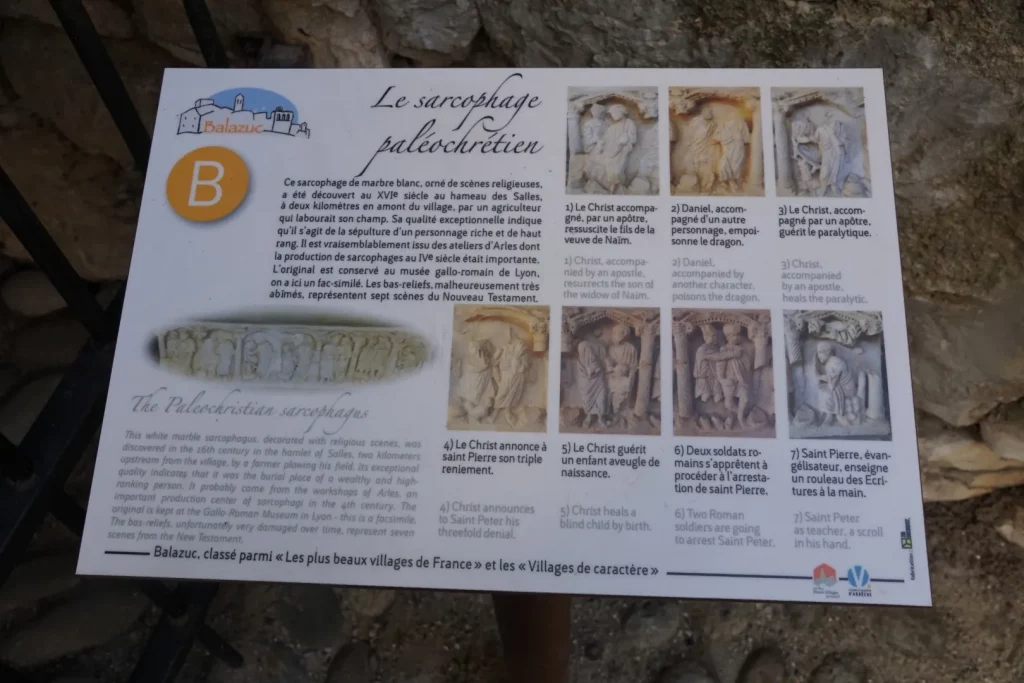

This trail starts from a parking area near the high end of the village – next to the « Tour Carré ». We wander though the old village streets, trying to keep our bearings and stumble across a variety of curiosities including the reproduction of an ancient sarcophagus discovered near Balazuc. (which like most other valuable historical artifacts is stored in a big city museum somewhere).

We are headed for the (one) bridge over the Ardèche river and the best way to find it is to always head downhill. The village is very quiet in winter and picturesque under raw winter light. (provided the sun is shining). The town is much more lively in the summer.

Eventually we cross the bridge and turn left to head down a riverside path to the once silent hamlet of Viel Audon. This spot, facing the Ardèche river and nestled under a good sized cliff is not reachable by road so at some point during the 19th or early 20th century its last inhabitants left for other places. In the second half of the 20th century the hamlet was brought back to life by dedicated local citizens who created an association aimed at rebuilding the village. For around the past 40 years the village has come to life in spring time and summer with students and youth groups from around Europe and elsewhere who live and work on restoration projects.

On this winter’s day, we saw a few goats and even fewer hikers.

Then we climb the ‘calade’ pathway to the top of the plateau and start a 4 to 5 km clockwise loop leading eventually back to the Ardèche river banks. The landscape on the plateau is best described as a chaotic mess of box trees, scrub oak and limestone rock forms created by differential erosion of hard and soft limestone. This plateau extends, in fact for about 50 km in a NE-SW orientation. Nothing but rocks and trees. The land is mostly useless for cultivation but was used for grazing livestock at various times. A few houses are scattered around in the vegetation. Many of them must be ‘off the grid’ : no municipal water or power, outdoor sawdust toilets, poor road access, etc.

Partway along the plateau route we pass behind the circular lookout tower. This tower sits on the right bank of the Ardèche river and once served to watch over a main approach route to Balazuc.

Back on the river edge we cross the bridge and climb up though the village by a different route admiring the old houses, the old fortification gates and the church with a bell gable (and no bell).

Winter is best for photography as the raw angled light provides great contrast and sharp outlines. On this day we were not that lucky – some sunshine but mostly dull cloudy skies.

For this circuit – walking sticks and solid hiking boots will help you defeat the large limestone rocks littering most of the route.